-

Section 01

Pātai 1: Te momo o te umanga Question 1: What type of agency

-

Section 02

Pātai 2: He pēhea te whaitake o ngā whakautu ki Pātai 1 ki te hanga ā-whakahaere Question 2: What do the question 1 answers mean for organisational form?

-

Section 03

Pātai 3: He umanga hou, he umanga kua tū kē rānei? Question 3: New agency or existing agency?

Well-informed judgements about organisational choice cannot jump from a general idea about an organisational role to a clear-cut decision on the most appropriate organisational form.

As with all high-quality policy advice, and with all consideration of machinery of government, there needs to be careful consideration of the context. There are 6 key sub-questions, outlined below, that should be worked through to consider what type of agency should undertake a particular role or function.

The analysis of agency type should clarify 2 main issues:

- What are the desirable governance and accountability arrangements for these functions and powers?

- What organisational form provides the best fit with the desired governance and accountability regime?

Because Public Service agency forms (department, departmental agency, interdepartmental executive board and interdepartmental venture) are so flexible and the most closely accountable to the Executive branch, we will require well-supported justification for any proposals for other forms.

Question 1(a): What role?

For central government

The starting point for analysis is that government is either already involved in an area of activity, or has decided as a matter of policy to become involved in that activity.

You should first consider if involving central government is (or remains) necessary or desirable, especially if the roles of central government, local authorities, non-government organisations (NGOs) or individuals have changed over time. If central government needs to be involved, what is the main role? For example, is it in policy, delivery, commissioning, regulation or another dimension of government activity?

Another important question is whether the activity is best situated in the executive branch of government or elsewhere? For example, the Office of the Ombudsmen (Office of Parliament, legislative branch) has some review and investigation functions in relation to the Corrections system that might otherwise have been located in an Independent Crown Entity.

For the agency undertaking the role

The next step is to identify what that government role would look like for an agency: for example, advisory, service delivery, regulatory, quasi-judicial, purchase or funding, trading, or financial institution. Many agencies carry out a mix of roles. This high-level categorisation of an agency’s primary role or roles informs, but does not determine, the most suitable organisational form for carrying out the agency’s activities. For example, a regulatory role may be discharged by a department or different types of Crown entities.

For the agency as a system participant

Most agencies in the public sector need to collaborate or co-ordinate their activities in some way with other government agencies and NGOs. Who the organisation needs to work with, (and how,) influences the appropriate governance arrangements, which in turn are critical to the choice of organisational form.

For example, basic sharing of information from time to time is not the same as a formal, ongoing commitment of agency resources to work on a joint strategy or programme alongside partner agencies, and where the level and type of joint working is critical to combined and individual success.

Our System Design Toolkit provides guidance and an overview of different forms of cross-agency working.

Question 1(b): What objectives and functions?

In addition to knowing what an agency’s overall role will be, a more detailed understanding is required of what the agency will actually do —, that is, its functions or day-to-day activities. For example, if a regulatory body is under consideration, will its functions include issuing licences to operate? What enforcement activities will it undertake? This understanding starts to build a picture of an agency’s profile in terms of the nature and scope of its activities, the impact of its functions, the variety of stakeholders, the sensitivities around ensuring that the activities are carried out appropriately, and the nature of risks if things go wrong.

If the agency’s objectives are subject to change, then a departmental form will have advantages over Crown entity forms (because objectives, functions and powers of Crown entities are specified, at least in broad terms, in statute).

Question 1(c): What powers?

Many agencies have specific powers to enable them to carry out their functions. For example, a regulatory body that has the power to issue a licence to operate usually has the power to suspend or revoke the licence if the operator fails in some way to observe the licence conditions. The nature and scope of an agency’s powers drive its governance and organisational form. Agencies that exercise coercive powers over private individuals (Police, Corrections, Oranga Tamariki) are generally kept as or within departments within the core Crown, whereas licensing powers and related enforcement may be devolved to Crown entities (sometimes even NGOs) through statute.

Question 1(d): What funding?

An agency’s profile includes its funding arrangements, from at least 3 perspectives:

- sources — general taxation, hypothecated tax, regulated fees or levies, trading revenue, co-funding with other parties or mix?

- how much — is it significant from a Crown perspective?

- sustainability — what are the longer-term intentions for ongoing funding? Are there risks to sustainability?

Another relevant funding question is whether the agency’s funds and liabilities should revert to the Crown if it is wound up (for example, Crown-owned companies’ debts would not fall on the Crown unless they were specifically guaranteed). Consult the Treasury.

Question 1(e): What risks?

An understanding of the risks associated with the agency’s functions and powers is also necessary. The key types of risk are:

- inherent or strategic risk — the relevance to the government and society of the activity, and the consequences if there is a performance failure or something adverse happens beyond the control of the agency

- political risk — in central government functions, the minister and the Government will usually be held responsible if things go wrong — ministers need to decide whether they prefer to exert close control or to seek to distance themselves by devolving the function

- fiscal risk — the potential for expenditure exceeding the appropriated Crown funding and/or financial loss (including from new obligations)

- contractual risk — how feasible is it to ‘contract’ for delivery of the function? Where activities have objectives or outputs that are complex, inherently difficult to specify or measure, or may need to be changed frequently, it can be difficult to legislate for their provision by a Crown entity, so a Public Service department may be a more appropriate form.

Legal risks are also important. For example, are the proposed functions consistent with relevant legislation or common law? Is legislation needed to give the agency relevant powers? What checks and balances might be needed when determining the most appropriate organisational form to perform the functions? Do functions need to be given separate statutory authority or placed in separate organisations?

Risks are generally viewed in terms of likelihood and potential impact. Whether an activity poses a high level of risk from the Government’s perspective is directly relevant to the governance and accountability arrangements that should exist between the minister and the agency.

Question 1(f): What governance?

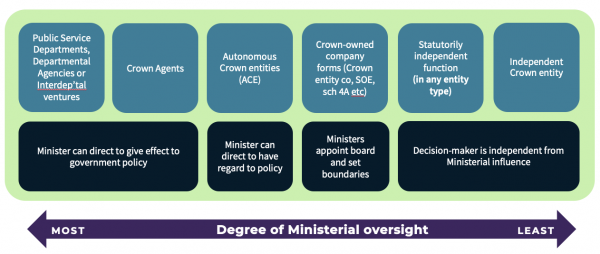

The essential question for public policy agencies is what degree of oversight the minister should have. This can be characterised broadly at 3 levels:

- a high degree of control or oversight or interaction, for example, in the development of policy

- a lesser degree of control or oversight and greater separation from ministers over decision-making

- clear separation from decision making, where the decision maker is independent from ministerial influence.

For each level of ministerial involvement, there is an associated package of governance arrangements that determine the feasible organisational design options.

Establishing agencies with specific statutorily independent functions is common across government, as illustrated in the table below.

|

|

What’s ministerial influence

|

What’s independent decision making by the agency |

|

Department (for example, Ministry of Social Development) |

Close relationship, and extensive powers of direction: MSD is a key deliverer of advice to government on social policy as well as one of its largest delivery agencies |

Decisions relating to the entitlements and interventions to be provided to any individual (based on statutory criteria) |

|

Crown Agent (for example, Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency) |

Arm’s-length relationship, but power to direct to give effect to government policy: Government Policy Statement sets out the overall allocation of funding for different classes of project |

Decisions to allocate funds to any particular project |

|

Autonomous Crown entity (for example, Public Trust) |

Arm’s-length relationship, but power to direct to have regard to government policy: for example, in relation to establishing group investment funds |

Decisions relating to administering estates, and fulfilling fiduciary obligations |

|

Crown-owned company (for example, NZ Green Investment Finance Ltd) |

Expectations as to where the public interest lies and the scope and nature of the investment portfolio |

Decisions to invest in/divest from particular companies or projects |