Aratohu tāpiri — mā te poari ā-umanga Supplementary guidance note — interdepartmental executive board

An interdepartmental executive board is a board of Public Service chief executives.

Defining an interdepartmental executive board

Interdepartmental executive boards draw together chief executives to deal with complex issues that have impacts and policy levers that sit across a wide range of portfolio areas. These complex issues cannot be solved by one single agency. These boards are a new model of public service agency. Public Service agencies are defined at section 10 of the Public Service Act 2020. They form part of the legal Crown, and operate under lawful instruction from ministers. They are distinct from other government entities that are outside the legal Crown and operate at arm’s length from ministerial control, such as Crown entities.

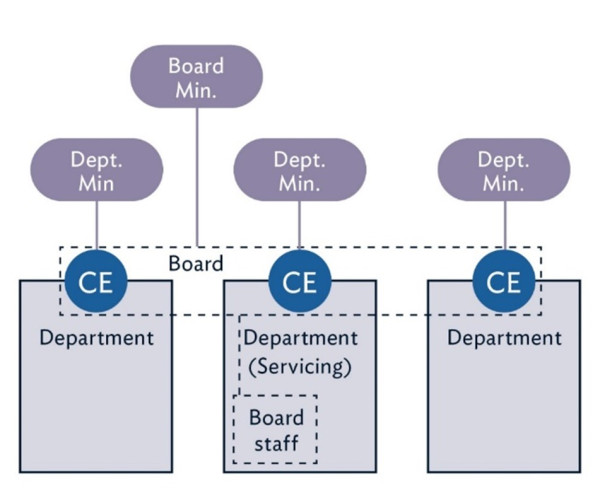

This model brings together chief executives of affected or contributing departments to work collectively. The board of chief executives aligns strategic policy, planning and budgeting around the shared issues within the remit of each of the chief executives’ agencies. Responsibility for delivery activities that contribute to the board’s priorities remain with individual departments. The prime minister designates a minister who is assigned responsibility for the board. Under section 28 of the Public Service Act 2020, members of the board are jointly responsible to that minister for the board’s functions (this relationship could be managed by the chair of the board). This is similar to how a Crown Entity board operates.

Section 28, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Interdepartmental executive boards can enter into contracts and administer appropriations.

The board can employ staff, who would be hosted by a servicing department which could also carry out administrative and reporting activities under delegation from the board.

Current interdepartmental executive boards are listed in Schedule 2, Part 3 of the Public Service Act 2020.

Schedule 2, Part 3, the Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Figure 1: Structure of an interdepartmental executive board

Background and objectives

In response to difficulties with cross agency working on complex problems, we designed a System Design Toolkit that demonstrates a spectrum of models for dealing with problems that cross agency borders (for example, social wellbeing). These models range from voluntary coordination at the soft end, to structural reorganisation (that is, mergers) at the hard end.

System Design Toolkit for shared problems

In the middle of the spectrum are models that involve groups of Public Service chief executives working together on a shared problem. These groups have existed as vehicles for cross-agency collaboration for some time, with varying degrees of formality and collective decision-making authority, from coordination of approaches, to more intensive formal collaboration. The goal of these groups is to work collaboratively through aligning strategic policy, planning and budgeting around shared goals or cross-cutting issues, without changing accountability for delivery activities.

Early board models improved information flows between agencies but suffered from many of the common problems of cross-agency activity in the Aotearoa New Zealand context, including agency prioritisation of vertical accountabilities to ministers, patch-protection and lack of commitment. The relatively large size of the boards also resulted in lack-of-ownership issues, with chief executives feeling little individual responsibility for problems in a group of, in some cases, more than 10 agencies.

The ‘specific purpose board’ model was developed as part of the 2012 Better Public Services reforms to address problems with voluntary collaboration board models and was intended as a Cabinet mandated mechanism for joint chief executive responsibility for specific cross-cutting policy issues. However, this model does not allow the board to employ staff, administer appropriations or enter into contracts. The interdepartmental executive board builds on this model to lock in resourcing and responsibility where it is necessary to hardwire these commitments.

When to use an interdepartmental executive board

The key uses of the model are to either:

- align strategy and planning activities for a group of agencies operating in overlapping policy areas

- harness the capabilities of individual departments to collectively plan for, and make funding decisions on, a specific cross-cutting problem or priority.

In these instances, responsibility for delivery activities that contribute to the board’s priorities would remain with individual departments.

The interdepartmental executive board is designed to work best where:

- 2 or more groups of functions or activities depend on each other to deliver a common objective or result (for example, complex interrelated policy areas, such as health and housing)

- the number of participating agencies is moderate (for example, 2 to 8)

- consensus about the objective is high (for example, around a shared government result)

- voluntary solutions have proven insufficient to resolve trade-offs between agency interest and shared interests

- the problem is large or important enough to warrant the additional priority, cost and time

- the problem is large or important enough to warrant having a minister assigned

- chief executives are willing to be jointly responsible for the problem.

When an interdepartmental executive board model is not useful

Interdepartmental executive boards should be applied selectively and only where there is potential for significant benefits from strengthened joint governance. Because a board requires formal establishment by Order in Council (as with a department), it is not suited to circumstances where:

- voluntary solutions have not yet been tested (these may prove sufficient means of collaboration, in which case an interdepartmental executive board is unnecessary)

- the policy and strategic context for the board is in a state of flux or unclear (there may be uncertainty over which departments should be included in the board’s remit, and which department is to act as the servicing department)

- the focus is on delivering services (in this case, an interdepartmental venture may be more appropriate)

- the issue is system-wide (there would be too many agencies involved)

- the objective is not a priority (the cost and ministerial involvement would be difficult to justify)

- the policy areas are straightforward or not interrelated enough to benefit from a dedicated board.

More information on other models for cross-agency work on shared problems can be found in the System Design Toolkit. This includes the specific purpose board — another form of chief executive board that is Cabinet mandated, rather than established through legislation (for example, the Social Wellbeing Board). These models should be considered during the organisational form policy process.

How an interdepartmental executive board works

Composition of the board and member responsibilities

Under section 27 of the Public Service Act 2020, an interdepartmental executive board operates in a similar manner to a chief executive of a department, in regard to day-to-day operations and performance of its functions. Decisions could be delegated to a director where appropriate (similar to how a Crown Entity board delegates to a chief executive).

Section 27, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Not all chief executives of agencies within the remit of the board will be members of the board. Under section 29(1) of the Public Service Act 2020, the Commissioner selects the members of the board from the chief executives included in the board’s remit. The remit is specified in the Order in Council establishing the board, and lists the departments with responsibilities in the subject matter area in which the board will work. Under section 26 of the Public Service Act 2020, departments within the remit can include departments, departmental agencies, the New Zealand Police, and the New Zealand Defence Force.

Section 26, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Section 29(1), Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

The board will need to ensure that its work programme is coordinated across other agencies within its remit and their chief executives.

Under section 28 of the Public Service Act 2020, the board reports directly to the board’s minister, and the members of the board are jointly responsible to that minister for the board’s functions and any joint resources it controls. In practice, the board may decide that the day-to-day relationship with the minister is managed by a particular individual (for example, the chair of the board or the director).

Section 28, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Chief executives on the board also retain their usual responsibilities and reporting lines to their ministers. The dual relationships will be managed by the chief executives on the board, who will work together to:

- provide joined up advice to the minister of the board

- carry out delivery through their own departments, for which they will be responsible to the appropriate minister for that department.

The chief executives on the board will also be responsible for briefing their individual ministers on the work of the board and any implications for their department.

Servicing department

To achieve the board’s objectives, they will likely need dedicated resource that can provide coordination across the various departmental policy areas and support the board to develop coherent strategic advice that balances various sector perspectives and trade-offs. The board can employ staff to a dedicated unit (similar to a secretariat) to support the board’s functions. The board can appoint a director to lead the work of this unit.

This unit is supported by a servicing department, which may be one of the agencies listed within the board’s remit. Under section 26(2)(c) of the Public Service Act 2020, the Order in Council establishing the board must list the servicing department.

Section 26(2)(c), Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

The board can also delegate administrative tasks (for example, legal, financial and human resource matters) to the servicing department, to reduce the administrative burden on board staff.

Responsibility for employees

An interdepartmental executive board is able to appoint and employ staff to the servicing department and has responsibility for individual personnel matters in respect of those employees supporting the board in its work (for example, appointment, transfer and personal grievances). Under sections 68 and 69 of the Public Service Act 2020, these responsibilities are delegated in legislation to the board from the servicing department which remains the legal employer.

Section 68, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Section 69, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

This means that the chief executive of the servicing department remains responsible for ensuring that some legal obligations to staff are met (for example, health and safety). The servicing department would likely support the board with administrative aspects of employment.

Independent advisers

Under section 29(3) for the Public Service Act 2020, the Public Service Commissioner may appoint one or more independent advisers (who are not Public Service chief executives) to the board.

Section 29(3), Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Independent advisers have no decision-making authority on that board. Independent advisers can be used to include those who cannot sit on the board as they are not part of the Public Service (for example, iwi or Crown entities). An independent adviser could also be placed on the board to provide technical expertise that does not otherwise exist within the board.

The provision for appointment of advisers by the Commissioner does not prevent the board from using its own advisers who are not appointed by the Commissioner.

Ministerial relationships

The key objective of an interdepartmental executive board is to take a collective approach to issues that span department and portfolio boundaries. The expectation is that ministers of the departments within the remit of the board also work collectively, such as jointly approving policies that have implications for the operation of individual departments. This would work in the same way that joint decisions between ministers currently work.

Financial management and reporting

An interdepartmental executive board can either administer its own appropriation or use appropriations administered by another department — this does not have to be the servicing department, but would most likely be a department within the remit of the board.

Under section 2 of the Public Finance Act 1989, an interdepartmental executive board is treated as a department, and can therefore administer appropriations under section 7C. This also means that an interdepartmental executive board has the same reporting requirements as a department, unless otherwise specified.

If the board administers its own appropriation, it will be responsible to the appropriation minister under the Public Finance Act 1989 for what is achieved with that appropriation, yet in practice may delegate the administrative tasks (such as the preparation of end-of-year performance reporting documents) to the servicing department (the Treasury website has detailed information about the responsibilities of an appropriation administrator).

A Guide to Appropriations — The Treasury

The board is responsible for ensuring that it complies with the reporting requirements under the Public Finance Act 1989. An interdepartmental executive board is required to provide its responsible minister with information on its strategic intentions (unless this requirement is waived by the Minister of Finance under section 41(3A) of the Public Finance Act 1989). A board is also required to prepare annual reports for each financial year. Again, the preparation of these reporting documents could be delegated to the servicing department, who would prepare separate strategic intentions and annual reports for the board (with involvement from the board where appropriate — for example, the signing of the statement of responsibility under section 45CA of the Public Finance Act 1989).

Section 41(3A), Public Finance Act 1989 — New Zealand Legislation

If the interdepartmental executive board manages assets and liabilities it will need to include financial statements in its annual report, unless this requirement is waived by the Minister of Finance. A waiver may be granted to the board only if the Minister of Finance considers the functions and operations of the board and the materiality of the assets, liabilities, expenditure, and revenue of the board does not justify the preparation of separate financial statements.

Section 45AB, Public Finance Act 1989 — New Zealand Legislation

Further guidance on the financial management and reporting requirements of interdepartmental executive boards is available on the Treasury’s website:https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/guide/public-finance-act-guidance-for-specified-agencies

Establishing an interdepartmental executive board

Consultation

Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission and the Treasury must be consulted about any proposal that might lead to the establishment of an interdepartmental executive board.

Cabinet decision

Prior to establishing an interdepartmental executive board, Cabinet decisions on the purpose of the board, scope of work, functions and any appropriations the board will administer, are required — as with any proposal to establish a new entity.

Order in Council

Once policy decisions have been made by Cabinet, an Order in Council is required under section 26 of the Public Service Act 2020, to establish the interdepartmental executive board (as is also required for a department or departmental agency). It must state:

- the name of the interdepartmental executive board

- the departments with responsibilities in the subject-matter area in which the board will work (the remit)

- the department that will be the servicing department of the board.

Section 26, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

Designation of board members

Under section 29, Public Service Act 2020, the chief executive members of the board are designated by the Public Service Commissioner from the chief executives of departments within the board’s remit (which will be listed in the Order in Council).

Section 29, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

The board does not need to include all of those chief executives. The Commissioner must also designate one of the members as the chairperson of the board. Before selecting board members or designating the chairperson, the Commissioner must invite the Minister for the Public Service and the minister for the board to identify any matters the Commissioner must take into account.

The Commissioner may also appoint independent advisers to the board.

Operating procedures

Under section 31 of the Public Service Act 2020, the interdepartmental executive board is required to develop operating procedures, which must be published online (for example, on the servicing department’s website, or a dedicated webpage for the board). These will set out the working arrangements between the board members, and will likely vary for each board. They may include aspects such as responsibilities of the chair, how many members make up a quorum, when the board meets, any rules on delegating attendance, how agendas are established, and how decisions are made. These procedures must include provision for the Commissioner to assist in the resolution of conflict if there is a breakdown of relationships.

Section 31, Public Service Act 2020 — New Zealand Legislation

System architecture and design

Appropriate structures, strong governance and clear accountability help the Public Service and wider public sector organisations to work together to deliver better outcomes for the public.