-

Section 01

Ministers’ Foreword

-

Section 02

Executive Summary

-

Section 03

An overview of progress to date — summary

-

Section 04

An overview of progress to date

-

Section 05

Factors in the success of the Action Plan so far

-

Section 06

Remaining challenges

-

Section 07

Appendices

-

Section 08

Further information

Ensuring gender remains a priority amongst challenges arising from COVID-19

Progress for women in employment depends on actively working to improve gender equity. This focus may waver under the pressures and resource constraints arising from COVID-19. However, because pandemics and economic shocks deepen existing inequalities, even more comprehensive action is now needed.

While closing the gender pay gap remains a priority, we also need to apply a gender lens to all workplace and employment decisions. Progress won’t be achieved through the delivery of a discrete work programme. The Taskforce will need to be responsive and agile to help agencies identify and consider all workplace decisions which impact women. Deliberate actions are required to support those who may be most negatively affected by COVID-19, including non-European women. Extra efforts are needed now to ensure that we maintain the gains achieved so far, and continue to progress towards gender equity so that women are less affected by economic shocks in the future.

Addressing bias

Gender pay gaps are a product of deeply embedded attitudes and beliefs about gender and work that affect the choices and decisions people make. The resulting biases affect the ways individuals think and behave at work and become embedded in policies and processes in workplaces.

Bias is difficult to detect, by those who benefit and by those who are disadvantaged. Adult behaviour is also hard to change, even when individuals are motivated to make a change. There is mixed evidence about the impact of unconscious bias training on the attitudes and ongoing behaviour of participants.[6] Addressing bias needs an approach that both influences individuals and facilitates structural change in organisations.

Addressing bias needs an approach that influences individuals and facilitates structural change in organisations

The Public Service’s 2020 Diversity and Inclusion programme, led by Papa Pounamu, strengthens and extends the Action’s Plan’s focus on gender bias. The programme expects all Public Service employees to complete bias awareness and cultural competency training and that all agencies will have bias training plans. Inclusive leadership guidance will be provided for all managers. Combining this training with the guidance developed by the Taskforce provides the tools to recognise and mitigate bias. For instance, policies which put checks and balances around manager discretion are central to decreasing the influence of bias.

Tackling the influence of bias requires ongoing efforts by individual managers and agencies. If agencies continue to review and monitor their progress in line with our guidance, they should be able to identify if, and when, they need to do more to address bias.

“Customs and the PSA worked really closely together to develop a programme of work around the gender pay gap Action Plan, so what's come across in the measures has been collaboratively designed.”

Sue Street, PSA Delegate, NZ Customs Service

Gaining traction at all management levels

Keeping all levels of agencies engaged is a challenge. We use a range of channels to reach leaders and the people implementing the Action Plan. Ultimately though, line managers have a lot of influence over the success achieved by agencies. Managers’ practice can be variable, for example with their level of comfort over flexible forms of working, even when the agency has a stated commitment to flexibility. A test of longer-term change is whether agencies can support all their managers to apply a consistent level of practice in all four focus areas of the Action Plan.

Addressing the compounding impacts of gender and ethnicity

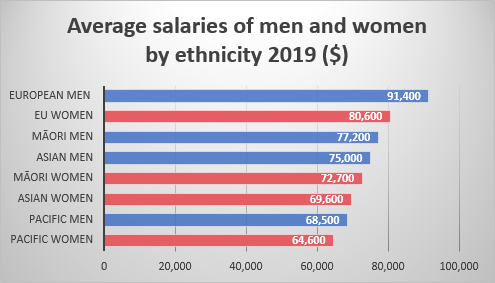

Gender and ethnic biases compound to create larger pay gaps for Māori, Pacific, Asian, and other non-European women. We can see this intersection in the graph below which shows that European public servants are paid the most on average and Pacific public servants are paid the least. Within every ethnic group, men are paid more than women. This pattern is consistent in the individual agencies that have analysed their pay for men and women by ethnicity.

Description of Figure 3

Figure 3 is a bar graph with eight bars. Each bar represents the average salary in 2019 for men or for women in one of four ethnic groups in the Public Service. The highest average salary at the top is for European men, and the lowest average salary at the bottom is for Pacific women.

The average salaries in 2019 in order from highest to lowest shown by the bars are:

European men $91,400

European women $80,600

Maori men $77,200

Asian men $75,000

Maori women $72,700

Asian women $69,600

Pacific men $68,500

Pacific women $64,600

Figure 3: Public Service average salaries by gender and ethnicity 2019[7]

Pay gaps for Māori and Pacific women are reducing: these women had the largest percent increases in average pay in the Public Service 2018–19, though there is still a long way to go.[8] Pay equity settlements for social workers at Oranga Tamariki and support workers at the Ministry of Education, contributed to these gains.

To reduce ethnic pay gaps, we need to address the combined barriers of gender and ethnic bias that these groups experience. Progress needs to be made for women from all ethnic groups in order for meaningful progress to be made on the gender pay gap overall.

To help tackle ethnic pay gaps, the State Services Commission is improving the quality of its ethnicity data and developing guidance on measuring ethnic pay, as part of its wider work to promote fairness, inclusiveness and diversity in the Public Service. We will ensure that the Action Plan and broader diversity and inclusion efforts are interconnected so that the compounding impacts of gender and ethnic bias experienced by Māori, Pacific and Asian women and other non-European groups is at the heart of both work programmes.

Pay equity

The purpose of pay equity is recognising the true value of work done by women in female-dominated occupations so that men and women receive equal pay for work of equal value.

In September 2018 the Government introduced the Equal Pay Amendment Bill (the Bill), to address systemic sex-based pay discrimination across female-dominated occupations. The Bill seeks to embed the Reconvened/Joint Working Group Pay Equity Principles (the Principles) to guide employees and employers through raising and resolving pay equity claims within New Zealand’s existing bargaining framework.

In 2017, the NZCTU and the State Services Commission agreed to apply the Principles to pay equity claims in the State sector in advance of the legislation being passed. In 2018 there were two pay equity settlements for female-dominated workforces in the State sector: social workers at Oranga Tamariki and Ministry of Education support workers. Another pay equity claim is close to settlement and a number of other claims are currently progressing using the Principles.

The Taskforce has developed a range of tools and resources, in consultation with agencies and unions, to assist parties to progress claims using the Principles. The Taskforce also advises a Central Agency Governance Group which provides assurance to Ministers and agencies on whether claim processes in the State sector are properly applying the Principles.

“When the pay equity settlement was reached, the impact on me and on the profession was huge. It righted the wrong, ensuring social workers at Oranga Tamariki were paid what they should have been paid.”

Bronwyn Pegler, Senior Practitioner, Oranga Tamariki

Embedding and sustaining change

Gender pay gaps are persistent: two years is a short time in which to make real shifts. We are grateful for the high level of engagement and commitment from agencies, and particularly for the support of agencies that have been working on their gender pay gaps for some years. However, we know that more work will be needed in future to further reduce gender pay gaps.

Agencies and unions are working towards a common goal under the Action Plan, but agencies were at different levels of readiness and therefore continue to be at different points on their journey. Ensuring that progress is consistent across all agencies requires a considerable effort from all involved. We hope that our emphasis on basing action on data analysis, collaborating with employees and unions, monitoring progress, and ongoing learning will help agencies embed and sustain the gains made to date.

Generating action in the wider State and private sectors

Employers’ willingness to address gender representation and pay issues has been growing in the last few years. This creates an opportunity for the experience and resources developed for the Public Service to be applied in the wider labour market.

A number of agencies outside of the core Public Service have opted to work towards the milestones in the Plan. These agencies could champion action in the wider State sector, and we have deliberately made our guidance public as the first step towards encouraging and supporting wider action. However, the size and diversity of organisations in the State sector present challenges to the depth of engagement we can achieve.

Many private sector organisations have been working to reduce their gender pay gaps for some time. Increasing transparency of their organisations’ gender pay gaps and related actions may encourage wider learning and action. To this end, members of the Champions for Change are piloting a standardised gender pay gap reporting template.

There are opportunities for the Public Service and private sector to build on each other’s learning. The Ministry for Women is supporting the National Advisory Council on the Employment of Women to facilitate sharing resources and knowledge across sectors through an e-seminar series on women in employment in mid-2020. The Ministry is also developing an online tool to build an understanding of gender pay gaps, and the Taskforce is launching an equal pay website later this year.

[7] See Public Service Workforce Data, Pay by gender and ethnicity

[8] Average pay for Pacific women increased by 6.3%, and for Maori women by 5.5%, in 2018–19